Andrea Cefalo is a Medieval fiction author and history blogger. Her debut novel, The Fairytale Keeper, was a quarter-finalist in Amazon’s 2013 Breakthrough Novel Contest. The sequel–The Countess’s Captive—was published earlier this year. She is currently working on the third book in her series.

Andrea Cefalo is a Medieval fiction author and history blogger. Her debut novel, The Fairytale Keeper, was a quarter-finalist in Amazon’s 2013 Breakthrough Novel Contest. The sequel–The Countess’s Captive—was published earlier this year. She is currently working on the third book in her series.

Though beauty standards have changed over the course of human history, the aspirations and efforts of women to meet these ideals remains largely unchanged. Today, the beauty industry is a multi-billion dollar enterprise that helps women pucker, pinch, pluck, and paint. At least modern women can count on agencies like the FDA to help keep harmful cosmetics off the market. Women living only a century ago weren’t nearly as fortunate and even though natural beauty was the standard and Queen Victoria declared makeup indecent, advertisements from the era prove beauty was a booming business. While some cosmetics and tricks from the Victorian Era were harmless, the lack of regulation led women to venture down some risky avenues—all for the sake of beauty. Ranging from disgusting to downright deadly, below are five of the strangest beauty trends and techniques from the Victorian Era.

1. Catching Tuberculosis

According to researcher Alexis Karl, the symptomatic pale skin of consumptives was associated with innocence, beauty, and above all else wealth. For those ladies who had to work outdoors a surefire way to keep pale was to catch TB. Contracting the Red Death had other beauty benefits, as well. The watery eyes, narrow waist, and translucent complexion of Tuberculosis victims was highly prized and women with the disease were considered extraordinarily beautiful. That being said, death by tuberculosis was pretty horrific, and it seems unlikely that any level-headed person would try to catch it on purpose.

Sleep and his Half-brother Death (1874) by John William Waterhouse.

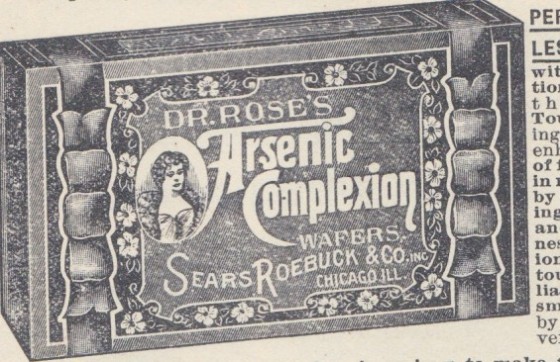

2. Eating Arsenic Wafers

Women believed eating these deadly supplements not only cleared their complexions, but also changed the shape of their faces by softening sharp features and disfigurements. In 1902, the Sears Roebuck catalog touted Dr. Rose’s French Arsenic Complexion Wafers as a cure-all, saying it possessed “the ‘Wizard’s Touch’ in producing, preserving and enhancing beauty of form… surely developing a transparency and pellucid clearness of complexion, shapely contour of form, brilliant eyes, soft and smooth skin…” The advertisement adamantly claimed that the amount of arsenic in these wafer “crafted by expert chemists” was completely safe. That’s likely untrue.

According to Andrew Meharg, an arsenic expert and professor of biogeochemistry at the University of Aberdeen, regular exposure to minute amounts of inorganic arsenic (10 parts per billion) increases a person’s risk for heart disease and cancer. On top of a long list of horrific side-effects—renal failure, epilepsy, and numbness to name a few—higher doses of arsenic caused the skin deformities that these wafers claimed to remedy.

Companies like Sears Roebuck claimed arsenic was safe for consumption.

3. Applying Mercury Eye Shadow

For the most part, Victorian women strived for natural beauty and ladies of high social standing rarely admitted to using make-up—though they most certainly did. The more brazen women wore thick eyeshadow—called eye paint—in shades of red and black. Respectable ladies lined their eyes subtly in similar shades. What was in this so-called eye paint? For starters, a substance called cinnabar was used to create vermillion red. It sounds innocent enough, but contains mercuric sulphide, which can cause kidney damage. Eye paints also contained lead tetroxide and antimony oxide, both of which are considered harmful to humans.

Toilet services like this, a gift from Napoleon to Josephine in 1810, sometimes hid cosmetics in secret compartments.

4. Dabbing Carmine on the Lips

Victorian women looking to add a little color to their lips often turned to a scarlet pigment called carmine. The pigment itself comes from the cochineal, a parasitic insect native to South America and Mexico. Most commonly, the pigment is extracted by grinding the insect bodies into a fine powder and then boiling them in ammonia. While carmine is rather disgusting, the dye only poses a threat to those who are allergic to it.

From strawberry toaster pastries to red velvet cake mixes, carmine dyes can be found in a variety of foods today. It is also commonly used in cosmetics and supplements. Consumer’s with an aversion to exoskeletons, can avoid it by checking the ingredient list on products before buying them. Carmine is also called Crimson Lake, Natural Red 4, C.I. 75470, Cochineal, and E120.

Cochineal were used to create red pigments in Victorian cosmetics.

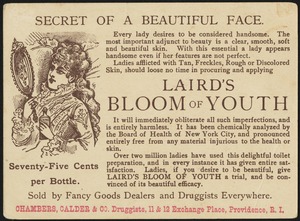

5. Whitening Skin with Lead Lotions

In order to rid themselves of freckles and blemishes, many Victorian women turned to corrosive face lotions. Though companies advertised that their “toilet preparations” were harmless, the American Medical Association begged to differ. In 1869, the AMA published a paper entitled “Three Cases of Lead Palsy from the Use of a Cosmetic Called ‘Laird’s Bloom of Youth’” which warned women of potential health risks from these so-called safe beauty treatments. Considering the face lotion contained lead acetate, it’s no surprise Laird’s Blood of Youth caused side effects such as paralysis, muscle atrophy, headaches, and nausea.

This ad falsely claims the safety of Laird’s Bloom of Youth.

Did you enjoy this article? An article entitled 5 More Deadly and Disgusting Beauty Trends is coming early next week. Follow the blog to make sure you don’t miss out.

Reblogged this on Mind: Raw and Uncut.

This was very interesting.

Ouch! Really interesting, thank you.

Pingback: 5 MORE Deadly and Disgusting Victorian Beauty Trends | THE WRITER-LY WORLD OF ANDREA CEFALO