When most people hear the name Peter Abelard, they think of Heloise and their affair. Some liken this romance between teacher and student to Romeo and Juliet. What began with forbidden love ended in tragedy and separation, but that is where the similarities end. So, for a special Valentine’s Day post, I’ve found five more interesting tidbits about the Middle Age’s most famous star-crossed lovers.

Abelard Was Looking for a Mistress Before He Met Heloise

Leighton’s Abelard and His Pupil Heloise. (1882)

Abelard didn’t step blindly into a teacher position and then fall for his pupil, Heloise. In fact, according to Pierre Bayle’s The Letters of Abelard and Heloise, Abelard admits in a letter that he had already been searching for a mistress to help him pass “agreeably those hours he did not employ in his study” and while several women had caught his attention, he was not looking for “easy pleasure.”

In a letter written years later to a man named Philintus, Abelard says, “I was ambitious in my choice, and wished to find some obstacles, that I might surmount them with the greater glory and pleasure.” This suggests some forethought on the part of Abelard when it came to an affair.

Abelard Planned to Seduce Heloise Before She was His Student

It appears that Abelard had interacted with or at least known of Heloise before he was her teacher. In the same letter written to Philintus, Abelard says a young woman in Paris caught his eye. She was indeed Heloise.

In that same letter, Abelard writes that “by the offices of common friends I gained the acquaintance of Fulbert [Heloise’s uncle and caretaker]; and can you believe it…he allowed me the privilege of his table, and an apartment in his house?” Later, Fulbert asked Abelard if he would tutor Heloise. Imagine the cannon’s excitement when one of France’s most respected scholars agreed to tutor his niece. It was during their lessons that Abelard convinced a reluctant Heloise to become his lover.

Heloise and Abelard May Have Been Kinky

Vignaud’s Abelard and Heloise Surprised by Master Fulbert. (1819)

Okay. This isn’t exactly a fact and it may be a stretch. Bear with me. Heloise and Abelard had sex in places that put them at high risk for getting caught. Did they do this to spice up their lovemaking? It’s possible.

Besides this, the pair may have had domination and submission fetishes. In his biography of Heloise and Abelard, James Burge claims Heloise felt wild freedom in completely surrendering to Abelard. Priya Jain, in an article for Salon magazine, suggests her submission to Abelard may have extended into their sex life. Abelard mentions physically punishing Heloise during her lessons. He also says Heloise was reluctant to have sex in a church refectory but did so after some convincing. We can only speculate whether this translates to fetish, but it seems plausible.

Some might argue that medieval women were generally submissive to men, especially their husbands and fathers. But Heloise was not your average medieval woman.

A Public Marriage Might Have Been Career-Suicide for Abelard

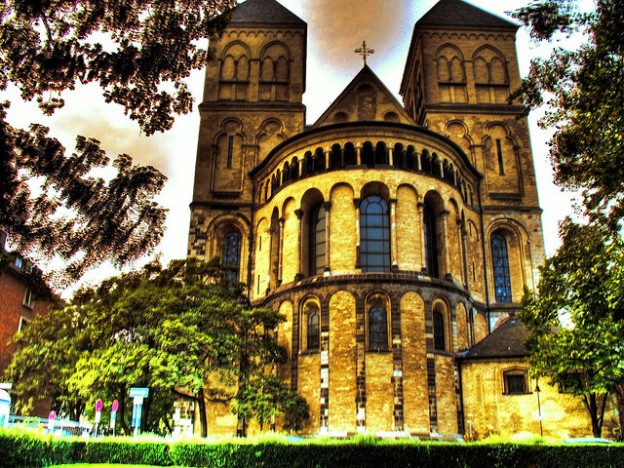

Cavelier’s Abelard. (1853)

In previous years, it was considered acceptable for lower clergy—such as a scholar attached to a Church—to have a wife or lover. But by the twelfth century, these scholars were held to the same vows of chastity as monks and priests.

This didn’t deter Abelard from his affair or even make him particularly cautious. As mentioned above, the pair had sex in places where they could have easily been caught— Fulbert’s bed chambers, a church refectory, and a convent kitchen, to name a few. Strangely, the affair did not cost Abelard his career, even though Fulbert was a well-connected canon in Paris. Sadly, it was Heloise who suffered the greatest consequence at first.

When Heloise got pregnant, she left Paris to live with Abelard’s sister in Brittany. There she gave birth to a son. Eventually, Heloise agreed to a secret marriage. This meant Heloise’s reputation remained tarnished and she had to live in a convent. Meanwhile, Abelard lived life as usual. Some historians suggest Abelard began losing interest in Heloise, which must have been devastating to the woman who gave up so much for him. Around this time, Fulbert hired a man to castrate the scholar. This not only put a quick end to the affair, it prevented any future affairs Abelard might have had. It also left him humiliated.

Heloise Was Incredibly Unconventional

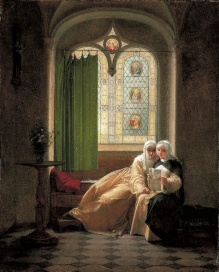

Mallet’s Heloise at the Abbey of Paraclete.(early 19th cent.)

For the most part, women—even those of higher status—were not as well-educated as their male counterparts. Abelard mentions that most women hated learning anything beyond needlework. Yet, Fulbert recognized his niece’s intellect and chose to nurture it. After all, Fulbert convinced one of France’s greatest scholars, Abelard, to instruct Heloise in philosophy. Even Abelard was impressed with her wit and how quickly she learned. Besides this, her well-written letters, rise to prioress, and unconventional yet logical arguments all speak to her intelligence and knowledge.

Heloise’s ideas about relationships were as counterculture as her education. Though it wasn’t exactly rare to have a child out of wedlock during the Middle Ages, it certainly wasn’t ideal. Most women would have married their lover for the sake of their reputation and that of their child. When Heloise’s pregnancy was made known, Fulbert insisted on a marriage and Abelard offered. Yet Heloise—at least initially—turned down the idea. She even recruited Abelard’s sister Lucilla to help convince him that

Abelard and Heloise. Manuscript Roman de la Rose. (14th cent.)

the marriage was a bad idea. In a letter to Abelard, Heloise says, “The name of mistress instead of wife would be dearer and more honorable for me…” In another letter, she says, “Even if I could be Queen to the Emperor and have all the power and riches in the world, I’d rather be your whore.”

Not only was her refusal unconventional, it was considered gravely sinful at the time and a risk to her soul’s salvation if she did not repent. Whether she decided to repent at some time in her life, I do not know. We do know that Heloise did submit to a secret marriage not long after the birth of their son, Astrolabe.

That brings up another unusual move on Heloise’s part. She named her son after an astronomical device invented by Muslim astronomers. During the Middle Ages, parents gave their children Christian names. For certain a bastard named Abelard would have drawn a few strange looks. Sadly, not much is known about their son.

Heloise’s lifelong devotion, while not exactly counterculture, is rather strange. One would think that after years apart, Heloise might have developed feelings of resentment towards Abelard. After all, Heloise had no desire to take holy orders, but she did at Abelard’s insistence. Yet, years later the two began a correspondence again that shows her undying affection for him and when Abelard died in 1142 at the age of 63, his remains were taken to Heloise who outlived him by 20 years. She asked to be placed in the same tomb as Abelard, but it is more likely that the two were entombed near each other. Later their remains were moved. Abelard and Heloise now rest side-by-side in Pere Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

Lenoir’s Tomb of Abelard and Heloise. (1817) Pere Lachaise Cemetery.

Andrea Cefalo is a Medieval fiction author and Medieval history blogger. Her debut novel, The Fairytale Keeper, was a quarter-finalist in Amazon’s 2013 Breakthrough Novel Contest. The sequel, The Countess’ Captive, was released in 2015. To keep up with her blog posts, upcoming novels, and musings, follow her on Facebook and Twitter or sign up for the VIP monthly newsletter.

Andrea Cefalo is a Medieval fiction author and Medieval history blogger. Her debut novel, The Fairytale Keeper, was a quarter-finalist in Amazon’s 2013 Breakthrough Novel Contest. The sequel, The Countess’ Captive, was released in 2015. To keep up with her blog posts, upcoming novels, and musings, follow her on Facebook and Twitter or sign up for the VIP monthly newsletter.

Works Cited

Abelard, Peter, and Heloise. The Letters of Abelard and Heloise. Trans. Betty Radice. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974. Print.

Bayle, Pierre. “Letters of Abelard and Heloise.” Project Gutenburg. N.p., 27 Apr. 2011. Web. 9 Feb. 2017.

Cavlier, Jules. Abelard. 1853. Stone Scultpure. Louvre Museum in Paris.

The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Heloise.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 20 July 1998. Web. 10 Feb. 2017.

Jain, Priya. “Lust, Revenge and the Religious Right in 12th Century Paris.” Salon. N.p., 18 Dec. 2004. Web. 8 Feb. 2017.

Leighton, Edmund Blair. Abelard and his Pupil Heloise. 1882. Oil on Canvas.

Lenoir, Alexandre. Tomb of Abélard and Héloïse. 1817. Tomb. Pere Lachaise Cemetery.

Luscombe, David Edward. “Peter Abelard.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 25 Mar. 1999. Web. 10 Feb. 2017.

Mallet, Jean-Baptiste Mallet. Eloise at the Abbey of Paraclet. Oil on canvas

Grasse, Musée Fragonard.

Nehring, Cristina. “Heloise & Abelard: Love Hurts.” Sunday Book Review. The New York Times, 13 Feb. 2005. Web. 7 Feb. 2017.

Vignaud, Jean. Abelard and Heloise Surprised by Master Fulbert. 1819. Oil on Canvas.

Andrea Cefalo is a Medieval fiction

Andrea Cefalo is a Medieval fiction

Andrea Cefalo is a Medieval fiction

Andrea Cefalo is a Medieval fiction

Andrea Cefalo is a Medieval fiction

Andrea Cefalo is a Medieval fiction

Without Walt Disney, I wouldn’t be a writer today. Not only has he inspired me to dream big, he is the reason I—and many others—love fairytales. Without him, I might never have learned to love the stories of Snow White and Cinderella. Without him, I might never have opened the pages to Grimm’s Fairytales and discovered The Three Army Surgeons and The Girl With No Hands. Without him, I would have never wondered where these stories came from and I would have never written The Fairytale Keeper series. I don’t know that most people can say Walt Disney changed the course of their lives like I can, but surely he brought some sense of whimsy and joy to all our lives. In my opinion, that is his biggest contribution—making millions of people happy and proving they too could follow their dreams.

Without Walt Disney, I wouldn’t be a writer today. Not only has he inspired me to dream big, he is the reason I—and many others—love fairytales. Without him, I might never have learned to love the stories of Snow White and Cinderella. Without him, I might never have opened the pages to Grimm’s Fairytales and discovered The Three Army Surgeons and The Girl With No Hands. Without him, I would have never wondered where these stories came from and I would have never written The Fairytale Keeper series. I don’t know that most people can say Walt Disney changed the course of their lives like I can, but surely he brought some sense of whimsy and joy to all our lives. In my opinion, that is his biggest contribution—making millions of people happy and proving they too could follow their dreams.