Andrea Cefalo is a Medieval fiction author and Medieval history blogger. Her debut novel, The Fairytale Keeper, was a quarter-finalist in Amazon’s 2013 Breakthrough Novel Contest. The next three books in The Fairytale Keeper series –The Countess’s Captive, The Baseborn Lady, and The Traitor’s Target—will debut later this year. She regularly posts about Medieval history on Facebook and Twitter.

Andrea Cefalo is a Medieval fiction author and Medieval history blogger. Her debut novel, The Fairytale Keeper, was a quarter-finalist in Amazon’s 2013 Breakthrough Novel Contest. The next three books in The Fairytale Keeper series –The Countess’s Captive, The Baseborn Lady, and The Traitor’s Target—will debut later this year. She regularly posts about Medieval history on Facebook and Twitter.

By the High Middle Ages political and economic systems in Europe became more complex, so too did the coins. For example, in part twelve of Ken Elks’ book, Coinage of Great Britain: Celtic to Decimalization, his charts show eighteen changes in Scottish coinage alone in a one hundred year period.

Historical fiction writers like myself try to paint the most accurate portrait of history that we can. I wanted to better understand the money of Medieval Germany so that I could better understand what my characters could earn and spend. The chart below serves to simplify a very complex system. I created it for myself, but I thought it might be of interest to others, so I am publishing it. Below the chart, I’ve listed a few facts worth considering before examining the table.

| Coin Name | Value | First Use | Description |

English: Penny English: Penny

|

1/240th pound of silver | Late 700s |

|

English: Groat English: Groat

|

|

1200s |

|

| English: Schilling

French: Sous German: Skilling Italian: Soldi |

|

700s |

|

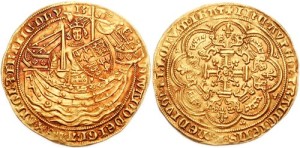

English: Noble English: Noble

|

|

|

|

| English: Mark

French: ? German: Mark Italy: ? |

|

700s |

|

| English: Pound

French: Livre German: Pfund? Italian: Lira |

|

700s |

|

- Coin values varied between nations. It’s similar to comparing an American dollar with the English pound or Euro. Each has a different value. The value of money in the Middle Ages was directly correlated with the coin’s size and silver or gold content, not the nation’s economic power.

- In general, German coins were of lower quality and value than English coins. The German lands consisted of duchies, counties, imperial cities, archbishoprics, and bishoprics. The Hohenstaufens doled out minting rights and didn’t regulate them. Therefore, many areas minted coins of varying quality. By the thirteenth century, six German pfennigs equaled four English pennies.

- During much of the early Middle Ages, the French kings were weak, and the kingdom itself was fairly small. While they minted purer coins than the Germans, the appearance varied widely. The mints of Tours in Touraine were considered the most stable.

By the end of the Middle Ages—much like the Scots—the French kings were constantly changing the coins and their value. Therefore, it is easier to classify the French coins into categories like types of pennies, types of big pennies (groats), and types of gold coins.

- As time passed and trade expanded into all classes, there was need for coins of larger and smaller denominations. The average pay for a day’s wages during the High Middle Ages was a penny. Let’s compare that to today where the average pay is about 100 dollars.

Imagine having to pay for everything with 100 dollar bills, except imagine that the 100 dollar bill was a coin. What if something costs 25 dollars? Then you have to chop the coin into fourths. It’s not very convenient. Here’s where it gets more complex: not every area minted the same denominations. However, most of them had a silver penny, a groat, and by the fourteenth century, a gold coin.

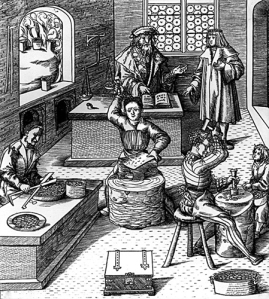

- Minters and noblemen got greedy or they went through difficult economic times and would devalue their own currency to keep the excess silver and gold. I discuss this more in a previous article: Inventing the Penny: Charlemagne’s Lost Effort at a Standard Currency.

Whether you’re a historical fiction writer or budding medievalist, I hope you found this chart of value. If you find any errors in my research, please comment.

Sources: “Banks and Money.” Currency and Banking in the Late Middle Ages. N.p., n.d. Web. 23 Oct. 2014.http://europeanhistory.boisestate.edu/latemiddleages/econ/banking.shtml Brooke, Christopher Nugent Lawrence. Europe in the Central Middle Ages: 962-1154. Harlow: Longman, 2000. Print. “Medieval Coin Denominations of Europe.” Medieval Coin Denominations of Europe. N.p., n.d. Web. 23 Oct. 2014.http://www.medievalcoinage.com/denominations/ “Medieval Sourcebook: William of Malmesbury: Counterfeit Money in the Time of King Stephen, 1140.” Internet History Sourcebooks Project. N.p., n.d. Web. 23 Oct. 2014. Mortimer, Ian. The Time Traveler’s Guide to Medieval England: A Handbook for Visitors to the Fourteenth Century. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011. Print. “The Fitzwilliam Museum : Coins and Medals Home.” The Fitzwilliam Museum News. N.p., n.d. Web. 23 Oct. 2014.http://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/coins/ “Testoon.” ø. Coin and Bullion Pages, n.d. Web. 03 Nov. 2014.

Pingback: Stretching a Medieval Penny: The Somewhat Empty Purse of a Medieval Shoemaker | Andrea Cefalo | Author of the Fairytale Keeper Series | Young Adult Historical Fiction