Few men are memorialized in such a contradictory manner as Konrad von Hochstaden. Surely a man who laid the cornerstone of one of Europe’s greatest churches—The Cologne Cathedral—should be remembered fondly. And he is…sometimes. (See the mosaic below.) But Hochstaden gave the people of Cologne and the Holy Roman Emperor of the time several reasons to hate him. Perhaps that’s why a vulgar statue of Hochstaden sits on the side of Cologne’s City Hall. (Scroll to the bottom to see it. Warning: it’s rather vulgar.)

This mosaic from Cologne’s Cathedral shows a saint-like Konrad von Hochstaden holding the plans for the church’s construction.

The Complexity of Rule in Thirteenth-Century Europe

To better understand Konrad von Hochstaden’s power and influence, a very brief examination of Medieval Europe’s political structure is in order. At the time, Europe was a hodgepodge of kingdoms, principalities, duchies (areas ruled by dukes), counties (areas ruled by counts), ecclesiastical sees (areas owned by the church), and free imperial cities. Trying to decipher the boundaries between these areas when looking at the map below is a tad tricky.

This map of Europe shows the political boundaries under Hohenstaufen rule.

Beginning in the tenth century, the king of the Holy Roman Empire was called King of the Romans and, later, King of the Germans. These were the titles used during Hochstaden’s lifetime. In a nutshell, prince electorates selected a nobleman to fill the position of king. Typically when a Holy Roman Emperor died, the pope promoted the King of Romans to take the emperor’s place, which essentially made the newly crowned Holy Roman Emperor the official ruler of Central Europe. Although, the amount of power each emperor actually wielded varied throughout medieval history and depended on several factors.

While inheritance often played a role in electing the King of the Romans and the Holy Roman Emperor, these were not strictly inherited positions. As I mentioned above, by the thirteenth century seven prince electorates—made up of four secular nobles and three church officials—ultimately decided who took the title of King of the Romans. The archbishop of Cologne was one of these prince electorates. One might argue that these kingmakers were even more powerful than the king himself. We certainly see this when examining the life of Konrad von Hochstaden, who was archbishop of Cologne from 1238 to 1261.

This miniature from the Chronicle of Henry VII (1341) shows the seven prince electorates. The archbishop of Cologne sits below the shield with the black cross.

Konrad Von Hochstaden’s Rise to Prince

Konrad von Hochstaden came from noble blood, his father being Count Lothar of Hochstadt. We know little of his childhood, but by 1216 he was the beneficiary of the parish of Wevelinghoven, and in 1226, he was promoted to canon. He eventually ended up in Cologne as the provost of the cathedral. When Archbishop Henry of Molenark died in March of 1238, the chapter named Konrad as his replacement, an appointment that Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II approved in August.Surprisingly, Hochstaden wasn’t even a priest at the time. That was a title he’d earned the following year.

Konrad Von Hochstaden was laid to rest in the Johannes Chapel of the Cologne Cathedral.

Konrad von Hochstaden Turns Against Frederick II

For the first year of his term as archbishop, Konrad supported the emperor in his disagreements with the pope, but when Pope Gregory IX issued Emperor Frederick’s (second) excommunication after he invaded a papal fief, Konrad’s loyalties shifted and he sided against the emperor with the pope and Archbishop of Mainz. It was a decision Hochstaden must have regretted in 1242 when he was badly wounded in battle against the emperor and captured by the Count of Julich, though he was eventually freed. By 1245, Konrad’s star was on the rise again.

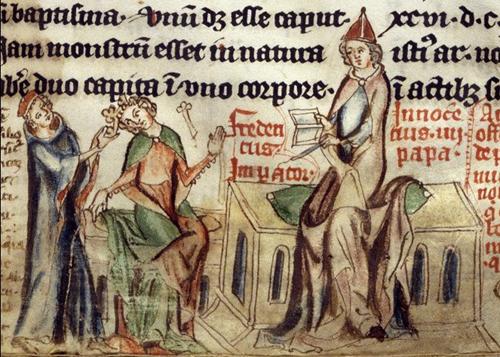

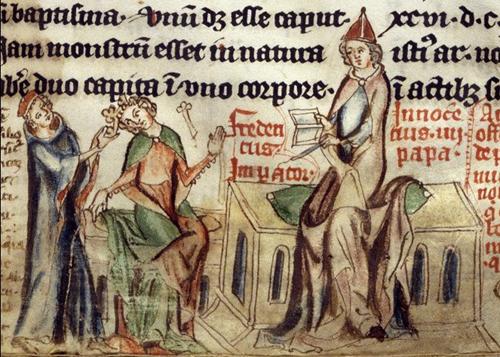

This fourteenth-century illumination portrays Pope Innocent IV excommunicating Emperor Frederick II.

Trouble in Cologne

By supporting the pope, Konrad von Hochstaden’s power grew. He now had two duchies and the ecclesiastical see of Cologne, making him the most powerful man in Northwest Germany. Not everyone was pleased with Konrad’s quick rise, and this resulted in struggles for power with his noble neighbors (Remeber the Count of Julich?) and the people of Cologne, who often refused to accept his authority. His ruthless methods in dealing with the people of Cologne left him with a malicious reputation.

Albertus Magnus (fresco, 1352, Treviso, Italy)

Hostilities grew, so a theologian and scholar by the name of Albertus Magnus was brought in to help bring the people of Cologne and the archbishop to peace. This event is referred to as the Great Arbitration. Konrad lost some power in the bargain. After which, he tried unsuccessfully to pit the craftsman against the patricians in order to gain favor. He died two years later, and when his successor, Engelbert II, tried to fortify one of the city’s towers, he was arrested and imprisoned by the Count of Julich for little over a year for violating the terms of the Great Arbitration. Meanwhile, Cologne gave way to violent battles between the wealthy families of Cologne. Unfortunately for Engelbert, he supported the losing side, and rather than continue his fight for Cologne, he abandoned it for his palaces in Bruhl and Bonn.

A league of German nobles defeated Engelbert’s successor, Siegfried of Westerburg, at the Battle of Worringen in 1288. After this, the archbishops of Cologne would no longer reside within the city walls. But Cologne would not officially have its freedom from the Church until 1475 when it was declared a Free Imperial City.

Battles for the Crown

Let’s go back to the battles between the Church and the emperor. In 1242, Frederick II selected Henry Raspe, Landgrave of Thuringia, and King Wencelaus of Bohemia as protectors of Germany until his young son Conrad was ready for the task.

A papal ban against Emperor Frederick was issued three years later. Raspe betrayed the emperor, siding with the pope, and was elected king in opposition to the boy he had earlier sworn to protect, Conrad. Henry experienced success on the battlefield, beating Conrad in the Battle of Nidda. Unfortunately for Henry, his reign was short. He died of illness only seventeen months after being named king.

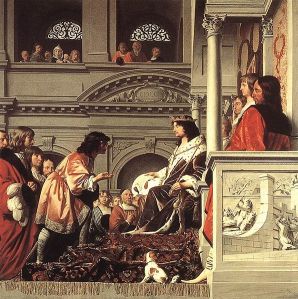

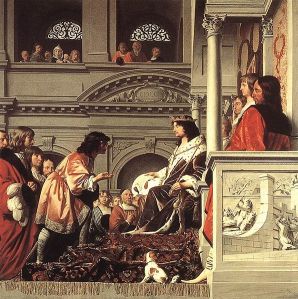

King William II of Holland Granting Privileges (Caeser Van Everdingen & Pieter Post, 1654)

Supposedly many noblemen were considered to fill Raspe’s shoes, but the anti-king crown fell to the young Count William of Holland. In April of 1248, Holland sieged Aachen, the place where German kings were traditionally crowned. It took six months for Aachen to fall, but when it did, it was the Archbishop of Cologne, not the Pope, who placed the crown on William’s head.

Konrad von Hochstaden’s faithful service to Pope Innocent was reward with the position of Apostolic legate in Germany, but Hochstaden reached higher. He secretly encouraged the people of Mainz to ask the pope to make him their new archbishop. This would make Konrad a double-prince elector since the Archbishop of Mainz also gets to vote on who becomes king. The pope gently denied Konrad the position, which caused Konrad to turn against the pope. The apostolic legation was taken from Konrad. Konrad turned from King William of Holland, as well and used every means necessary to dethrone him. He probably would have succeeded if William hadn’t died first.

After the death of King William, it was time for Konrad to find another king. His vote fell to Richard of Cornwall, brother to King Henry III of England. In trade for his support, Konrad was gifted full imperial authority over his principalities and the right to name bishops in Richard’s stead. Konrad von Hochstaden died four years later. Ironically, his remains lie in the Cathedral of the city where he was most hated: Cologne.

I hope you enjoyed this article on Konrad von Hochstaden. Hochstaden plays a key role in my medieval fiction series, The Fairytale Keeper. This article is a part of a series on real historical figures from the time period who appear in The Fairytale Keeper series. As promised, here is that vile statue of Konrad von Hochstaden.

Andrea Cefalo is a Medieval fiction author and history blogger. Her debut novel The Fairytale Keeper, was a quarter-finalist in Amazon’s 2013 Breakthrough Novel Contest. The sequel–The Countess’s Captive—was published earlier this year. She is currently working on the third book in her series.

Andrea Cefalo is a Medieval fiction author and history blogger. Her debut novel The Fairytale Keeper, was a quarter-finalist in Amazon’s 2013 Breakthrough Novel Contest. The sequel–The Countess’s Captive—was published earlier this year. She is currently working on the third book in her series.

Did you enjoy this article? Well, there’s more where that came from! Check out the archives or peruse the sidebar for a list of trending posts. To make sure you don’t miss out on my latest articles, follow this blog or sign up for the newsletter.

And if you happen to be a historical fiction reader who loves a strong female voice and gritty Medieval settings, check out The Fairytale Keeper series. (When a storyteller’s daughter attempts to avenge her mother, she gets caught in the cross-hairs of a power struggle between kings and kingmakers. The conflict gives rise to some of the greatest stories ever told: Grimm’s Fairy Tales.) Publisher’s Weekly calls The Fairytale Keeper a “resonant tale set late in the 13th century…with unexpected plot twists. An engaging story of revenge.”

Further Reading and Sources:

34.717944

-82.324265

Andrea Cefalo is a Medieval fiction

Andrea Cefalo is a Medieval fiction